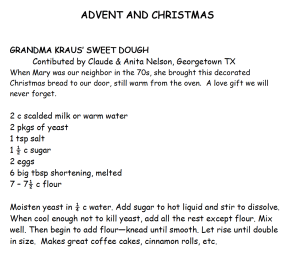

Dumbarton United Methodist Church

Inaugurated before the official creation of the Methodist Church, Dumbarton United Methodist Church is one of the oldest continuing Methodist congregations in the world. It has been a part of Georgetown continuously since 1772, meeting first in a cooper’s shop near the riverfront, then on Montgomery Street (now 28th Street), and finally at the present site on Dumbarton Avenue in 1849. When the church was remodeled in 1898, it acquired its present neo-Romanesque front, and the stained glass windows were installed from 1898 to 1900.

Dumbarton United Methodist Church Famed Stain Glass Windows

Religious Persecution

Methodism was not a mainstream religion at the time. In 1775, Philip Gatch, one of the traveling preachers assigned to our Georgetown congregation was “attacked by two men who forced him into the inn to drink liquor. He steadfastly refused, and the men fell into a quarrel between themselves, so that he was able to get away.”

Tarred for his religious beliefs:

Later, Philip Gatch was tarred for his religious beliefs between Baltimore and Frederick. “The last stroke made with the paddle with which the tar was applied was drawn across the naked eyeball, which cause severe pain, from which I never entirely recovered…. When I go to my appointment the Spirit of the Lord so overpowered me that I fell prostrate in prayer before Him for my enemies. The Lord, no doubt, granted my request, for the man who put on the tar and several others of them were afterward converted.” From “A Historical Adventure Into a Noble Past” (1958) by Harold Hutchinson and Rev. William C. Taylor.

Dumbarton United Methodist Church

A Part of Georgetown, Washington, DC History

Originally a tobacco port and settled by Scotch immigrants, Georgetown in Washington DC was a busy and successful center of business until a massive flood in 1889, and six years later lost its status as a port of entry into the United States.

Georgetown teemed with blacksmiths, boat builders, teamsters, wharf workers and their families. Millers eventually replaced tobacco traders as wheat replaced tobacco as Georgetown’s primary cash crop. Mills run by waterpower lined the Georgetown waterfront at the time.

By 1915, Georgetown was considered out of the way, unfashionable and run-down. Preservation movements in the 1930s began to reverse that. See Washington At Home: An illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation’s Capital. Windsor Publications, Inc., Northridge, California, 1988.

Humble Beginnings

The congregation that was to become Dumbarton was originally not Methodist, not a church, and not named Dumbarton. It began in a barrel makers’ shop with a small band of the faithful hosting their first permanent appointment of a traveling pastor on Christmas eve, 1772. This group, calling itself the “Georgetown Society,” was drawn to the shouting, Bible-thumping evangelism of circuit-riding preachers who traveled up and down the mid-Atlantic on horseback, preaching that rich and poor, young and old, could be saved by a faith that called on them to renounce their sinful ways. For one of our parishioner’s sometimes irreverent impressions of Dumbarton’s and Methodism’s unlikely beginnings, click here.

The American Revolution

The Georgetown Society didn’t fare well during this period. Its members were affiliated with the Church of England, and John Wesley, Methodism’s founder, was an outspoken Tory. The Society itself was divided over independence for the American colonies.

Francis Asbury, the founder of Methodism in the United States, visited the budding congregation several times during its first few decades as he guided a fledgling American Methodism to independence from Wesley, who wanted it to remain within the Church of England. Asbury tried to remain apart from the issue of political independence, emphasizing individual, not societal change.

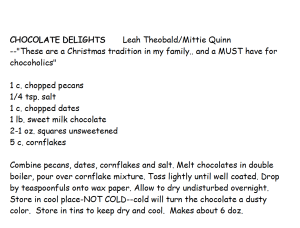

Stained Glass Window Dedicated to Foxall at Dumbarton United Methodist Church

A leading figure in the early church was Henry Foxall, whose Columbia Foundry produced 300 cannons and 30,000 shot per year for the nation’s defense in the early 1800s. A mayor of Georgetown and a lay preacher himself, Foxall contributed large amounts of money to support the Georgetown church. Once, when asked about his inconsistent roles as proclaimer of the gospel of peace and armorer of wars, he replied, “If I do make guns to destroy men’s bodies, I build churches to save their souls.”

The Montgomery Street church, built in 1795, enjoyed the preaching of some of the best circuit riders of the early Methodist church. It was here where John Hersey, the first Methodist missionary to Africa, was converted in 1809.

Before the Civil War

African-Americans, some of them held in bondage by White members, were seated in the balcony of the church for its first several decades. But many Black members split off to form Mount Zion Church in 1813, while others continued to attend what became the Dumbarton Avenue Methodist Church after construction of the current building on that street in 1849.

From 1846 to 1848, Dumbarton’s junior pastor was William Taylor, who went on to become one of Methodism’s most important missionaries. From Dumbarton, he and his wife sailed to California to establish the second Protestant church in the new state in 1849. Over the next four decades, he was to found successful missions in Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, Peru, Chile, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Brazil, capping his career by becoming the first missionary bishop to Africa.

Civil War Years

When the Civil War broke out, Dumbarton’s congregation was deeply divided, sending its men to both Union and Confederate armies. After the Second Battle of Bull Run in 1862, the church was converted to a hospital as thousands of casualties streamed into the city. Legend has it that Walt Whitman came there to read to the wounded, as he was known to have done at other field hospitals. But only Dumbarton oral tradition supports this story.

On March 8, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln visited Dumbarton for its first worship service after its decommissioning as a hospital. The sermon was delivered that day by Lincoln’s friend, Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson. The Washington Star reported that Lincoln was “much affected by the sermon, being moved to tears.” For a contemporary parishioner’s dramatization of Lincoln recalling that Sunday months later as he gathered his thoughts for the Gettysburg Address that fall, click here. As for Dumbarton’s slaveowners, many were compensated for freeing their slaves by the District of Columbia by the DC Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862.

After the Civil War

After the war, Dumbarton continued to serve residents of Georgetown, but in 1871, Georgetown itself ceased to exist as a separate city and became part of Washington, DC. In 1895, the identity of Georgetown was further obscured by the renaming of streets to fit the DC system giving streets number or letter designations. Somehow Dumbarton Avenue escaped this redesignation, although it was later renamed Dumbarton Street. In 1898, the church building was remodeled, expanded, and given the facade that adorns it today.

Dumbarton’s membership expanded rapidly in the late 19th century as the Methodist Episcopal Church surpassed other Protestant denominations in size. Dumbartonians joined in the camp meeting trend of out-of-town retreats to promote salvation and recruit more members. But Dumbarton’s growth stalled near the turn of the century as Georgetown’s industries moved to other parts of the metropolitan area and took church members with them.

In 1913, a chapter of the Knights of the Holy Grail was created by 15 young men to study the possibilities of careers in Christian service. During World War I, a Sunday evening meeting of the “Soldiers and Civilians Social Hour” met as a response to the large number of young men and women in Washington, DC.

The Great Depression led to increased activity at Dumbarton United Methodist Church with the Epworth League, the Women’s Society for Christian Services and the Teacher’s Training Class.

Methodist Leadership in Washington, DC

Dumbarton’s membership expanded rapidly in the late 19th century as the Methodist Episcopal Church surpassed other Protestant denominations in size. Dumbartonians joined in the camp meeting trend of out-of-town retreats to promote the religion. But Dumbarton’s growth stalled near the turn of the century as Georgetown’s industries moved to other parts of the metropolitan area and took church members with them.

World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II

Along with the rest of the country, some members of Dumbarton lost their lives to World War I, the 1918-19 flu epidemic and World War II. Dumbartonians also felt the impact of the Great Depression, helping those in need with financial and moral support. Dumbarton also remained active in discouraging alcohol consumption, even to the end of Prohibition.

Later, as cars and suburban living became more and more affordable, many Dumbarton parishioners moved and joined churches in the suburbs. By 1940, the church’s membership had dwindled in number and wealth to the point where it had only 65 cents in its bank account. By any measure but spiritual, it was at death’s door.

During World War II, 46 Dumbarton Church members served in the armed forces, with three giving their lives.

Looking Outside Our Walls –From the ‘60s to the Present

As it lost its ability to serve as a neighborhood church, Dumbarton slowly began to draw college students from Georgetown and nearby areas and social activists from the suburbs to renew itself. Previously nonpolitical, the church immersed itself in civil rights marches, peace rallies, and local and world affairs, carving out a national reputation as a leader in progressive Christianity. One Dumbartonian, Mike Beard, headed the National Coalition to Ban Handguns, for example, in an office provided and financially supported by the national United Methodist Church in the 1970s and 80s.

Sanctuary for Undocumented Migrants

Sanctuary for Undocumented Migrants

Providing Sanctuary for a Salvadoran Asylum Seeker

In 1985, Dumbarton helped a Salvadoran refugee enter the country illegally. The cause was part of the national sanctuary movement in which churches defied national law by sheltering undocumented refugees fleeing political persecution. Our special guest, formerly head of the El Salvadoran Mothers of the Disappeared, promptly began exposing the dark side of U.S. support for Central American dictatorships at churches and college campuses across the country. After her eventual arrest, Dumbarton hired legal counsel to win her political asylum and a green card.

Church members also took numerous mission trips to Latin America and Palestine from the 1980s through the turn of the century to observe conditions, help ameliorate them, and recommend changes in U.S. policy.

A Musical Protest against Nuclear Arms

Toward the end of the 1980s, Dumbarton families performed a traveling musical, Alice In Blunderland, for several years at area schools and churches calling for international nuclear disarmament.

Widening the Circle to Make a Place for LGBTQ People

Dumbarton United Methodist Church at Trans Rights Rally

Dumbarton became a reconciling congregation in 1987, (part of RMN – Reconciling Ministries Network) inviting gay men and lesbians into the life of our church. Over the years, we have widened our welcome to include bisexual, transgender, non-binary, gender-queer, and questioning people…and the process continues. The more we learn about sexual orientation and gender identity, the more our inclusion has expanded. Since 1987, many LGBTQIA+ people and their families, friends and allies have been, and continue to be, vital in the life of this congregation, appreciating the opportunity for every person to bring all of who they are to church.

When the District of Columbia legalized same-sex marriage in 2009, Dumbarton was there. We became the first United Methodist congregation in the city to agree to perform such weddings–openly celebrating love and loyalty in all marriages–in direct defiance to United Methodist policies. In 2015, when the Supreme Court ruled that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples, Dumbarton was there, clergy & laity, celebrating and offering communion on the steps of the Supreme Court building. We continue to advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and for full inclusion in the United Methodist denomination and in the wider world.

Becoming an Anti-Racist Church

In 2020, following the murder of George Floyd and the racial justice uprisings around the country, Dumbarton pledged to deepen our commitment to justice and inclusion and work towards becoming an Anti-Racist Church. We signed on to the pledge to embody anti-racism, acknowledging that:

- the sin of racism has been destructive to the unity of the church throughout its history;

- racism continues to cause painful division and marginalization in the church and the world;

- we shall confront and seek to eliminate racism, whether in organizations or in individuals, in every facet of the church’s life and in society at large.

Read more about the pledge to embody Anti-Racism on the Baltimore-Washington Conference webpage.

Read more about the steps we are taking to embody Anti-Racism at Dumbarton.